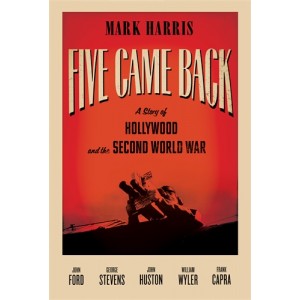

At the height of their respective careers, five Hollywood directors—John Ford, William Wyler, John Huston, Frank Capra, and George Stevens—went to war. Their patriotism never in question, their motives for enlisting were not entirely altruistic. Capra claimed to have been bored with his success. Ford was not without vainglory and enjoyed the trappings of naval life. Like a character in a picaresque novel, Huston seemed predisposed to adventure from the day he was born. Only Wyler and Stevens seemed to have faced some kind of existential crisis in the run-up to war: Wyler had left family behind in Europe; while Steven’s melancholy temperament was at odds with his showbiz beginnings. A maker of “champagne” comedies and Laurel and Hardy two-reelers, Stevens filmed the liberation of Dachau. That’s one hell of a journey in itself, but Mark Harris gives us the equivalent of five biographies in one, as well as a history of Hollywood over a tumultuous decade (1938 – 1947). Impeccably researched, beautifully written, and organised with great narrative economy, Five Came Back plays like a studio-era best picture nominee: Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives comes to mind.

Wyler’s Academy Award winner drew on his experience overseas, as well as his return to civilian life. In fact, of the five men, only Capra was stationed at home for the duration of the war. Ford, renowned for his immaculate framing and elegiac myth-making, was present at the Battle of Midway, in 1942, and at Omaha Beach two years later. Framing and composition went out the window: what Ford (and his unit) captured with 16mm cameras ushered in a new era of war on film. There was nothing elegant or elegiac about it. But contemporary cinema still reverberates from the shudder and shake of Ford’s footage. Saving Private Ryan’s opening 25 minutes would not exist without the repository of images personally filmed or supervised by this self-proclaimed maker of Westerns. Ford, who could be boastful and belligerent (when drunk), had told the men working under him: “If you see it, shoot it.” George Stevens told his men to “never look away”. Leading by example, Stevens didn’t, though what he saw — and preserved on film — haunted him forever. Huston’s influence, meanwhile, can be felt in Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master: the early scenes at a veterans’ hospital clearly drawing on Huston’s Let There Be Light, his documentary about returning traumatised soldiers. Huston’s film was banned by the US Government until 1980. Stevens’s footage of Dachau was also kept under lock and key, though the decision was personal rather than institutional – which perhaps tells you something about the sensitivity of the man: his attempt to shoulder the burden of what he had witnessed was ultimately too much.

I closed Harris’s book with a sigh, moved not only by the sad ending but by the author’s own considerable narrative gifts. Harris wraps up his story with the skill of an old Hollywood pro, something that all of these men, and the studio heads they worked for, would have appreciated. But he never lets us forget that some pictures — “best” or otherwise — came at a considerable cost.

—MM

A slightly different version of this review appeared in the Curzon Magazine dated September/October 2014.

http://www.curzoncinemas.com/news/all/curzon_magazine_issue_46.aspx