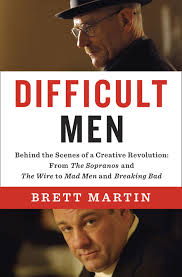

News that Robert Towne has joined Mad Men’s writing staff would seem to confirm the premise of Brett Martin’s Difficult Men: that television—especially premium cable—is now more receptive than Hollywood to the kind of work that Towne and his contemporaries routinely produced between 1967 – 1980. In Martin’s view, the programmes made during the “third Golden Age of television” are as challenging and ambitious as anything that came out of “the New Hollywood”; and that those “difficult men”—Tony Soprano, Don Draper, Omar Little, Walter White—are as compelling and as morally complex as the 1970’s anti-heroes. It’s not a new argument, but Martin’s is the first book to articulate the reasons—creative, sociological, financial, and technological—for such a seismic shift.

Martin frames his narrative as though it, too, was a long-form television series. He profiles the “showrunners”, that new breed of auteur, who can be as difficult and as driven as their creations. Each writer gets a clearly defined ark, and while the book favours the creators of The Sopranos, The Wire and Deadwood—David Chase, David Simon and David Milch respectively—and gives stand-alone episodes, or chapters, to Matthew Weiner (Mad Men) and Vince Gilligan (Breaking Bad), it is Chase who emerges as the book’s leading “difficult” man. The Sopranos, after all, changed everything. Martin cites the three Davids as examples of the writer as Trojan horse: they took well-established formats—the mob drama, the police procedural, the Western—and smuggled their dark dreams into our living rooms, and on to our laptops. For we’re part of this story too: our viewing habits—not only what we watch but the way we watch—have been crucial to the success of the “third Golden Age”: streaming, on-demand, the pleasures and convenience of the box set. We’re all schedulers now.

But there are self-imposed limits to Martin’s argument, implicit in the book’s title, and which he acknowledges in his introduction: there is little or no room for women—Sex and the City and Girls get the briefest of walk-ons. And while comparisons with Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls are not unfounded—a tendency to dish the dirt, a fondness for macho grandstanding—Martin’s book is actually closer in spirit to Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution. That book, through its wonderful framing device, told the story of how Towne’s generation took advantage of the studio system’s decline; Martin tells a similar story, though one in which a “much maligned medium”—television—is now at the forefront of American filmmaking. The size of the screen and the means of delivery might have changed, but these “difficult men” have been making movies all along.

—MM